Positive-definite kernel

In operator theory, a branch of mathematics, a positive definite kernel is a generalization of a positive-definite matrix.

Contents |

Definition

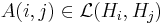

Let

be a sequence of (complex) Hilbert spaces and

be the bounded operators from Hi to Hj.

A map A on  where

where

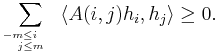

is called a positive definite kernel if for all m > 0 and  , the following positivity condition holds:

, the following positivity condition holds:

Examples

Positive definite kernels provide a framework that encompasses some basic Hilbert space constructions.

Reproducing kernel Hilbert space

The definition and characterization of positive kernels extend verbatim to the case where the integers Z is replaced by an arbitrary set X. One can then give a fairly general procedure for constructing Hilbert spaces that is itself of some interest.

Consider the set F0(X) of complex-valued functions f: X → C with finite support. With the natural operations, F0(X) is called the free vector space generated by X. Let δx be the element in F0(X) defined by δx(y) = δxy. The set {δx}x ∈ X is a vector space basis of F0(X).

Suppose now K: X × X → C is a positive definite kernel, then the Kolmogorov decomposition of K gives a Hilbert space

where F0(X) is "dense" (after possibly taking quotients of the degenerate subspace). Also, ⟨[δx], [δy]⟩ = K(x,y), which is a special case of the square root factorization claim above. This Hilbert space is called the reproducing kernel Hilbert space with kernel K on the set X.

Notice that in this context, we have (from the definition above)

being replaced by

Thus the Kolmogorov decomposition, which is unique up to isomorphism, starts with F0(X).

One can readily show that every Hilbert space is isomorphic to a reproducing kernel Hilbert space on a set whose cardinality is the Hilbert space dimension of H. Let {ex}x ∈ X be an orthonormal basis of H. Then the kernel K defined by K(x, y) = ⟨ex, ey⟩ = δxy reproduces a Hilbert space H. The bijection taking ex to δx extends to a unitary operator from H to H' .

Direct sum and tensor product

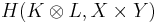

Let H(K, X) denote the Hilbert space corresponding to a positive kernel K on X × X. The structure of H(K, X) is encoded in K. One can thus describe, for example, the direct sum and the tensor product of two Hilbert spaces via their kernels.

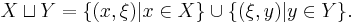

Consider two Hilbert spaces H(K, X) and H(L, Y). The disjoint union of X and Y is the set

Define a kernel

on this disjoint union in a way that is similar to direct sum of positive matrices, and the resulting Hilbert space

is then the direct sum, in the sense of Hilbert spaces, of H(K, X) and H(L, Y).

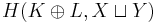

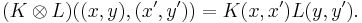

For the tensor product, a suitable kernel

is defined on the Cartesian product X × Y in a way that extends the Schur product of positive matrices:

This positive kernel gives the tensor product of H(K, X) and H(L, Y),

in which the family { [δ(x,y)] } is a total set, i.e. its linear span is dense.

Characterization

Motivation

Consider a positive matrix A ∈ Cn × n, whose entries are complex numbers. Every such matrix A has a "square root factorization" in the following sense:

- A = B*B where B: Cn → HA for some (finite dimensional) Hilbert space HA.

Furthermore, if C and G is another pair, C an operator and G a Hilbert space, for which the above is true, then there exists a unitary operator U: G → HA such that B = UC.

The can be shown readily as follows. The matrix A induces a degenerate inner product <·, ·>A given by <x, y>A = <x, Ay>. Taking the quotient with respect to the degenerate subspace gives a Hilbert space HA, a typical element of which is an equivalence class we denote by [x].

Now let B: Cn → HA be the natural projection map, Bx = [x]. One can calculate directly that

![\langle x, B^*By\rangle = \langle Bx, By\rangle_A = \langle[x], [y]\rangle_A = \langle x, Ay\rangle](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/721714efe1fa699afc87ef25daec9163.png) .

.

So B*B = A. If C and G is another such pair, it is clear that the operator U: G → HA that takes [x]G in G to [x] in HA has the properties claimed above.

If {ei} is a given orthonormal basis of Cn, then {Bi = Bei} are the column vectors of B. The expression A = B*B can be rewritten as Ai, j = Bi*Bj. By construction, HA is the linear span of {Bi}.

Kolmogorov decomposition

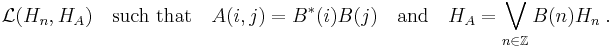

This preceding discussion shows that every positive matrix A with complex entries can expressed as a Gramian matrix. A similar description can be obtained for general positive definite kernels, with an analogous argument. This is called the Kolmogorov decomposition:

- Let A be a positive definite kernel. Then there exists a Hilbert space HA and a map B defined on Z where B(n) lies in

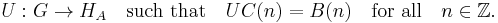

The condition that HA = ∨B(n)Hn is referred to as the minimality condition. Similar to the scalar case, this requirement implies unitary freedom in the decomposition:

- If there is a Hilbert space G and a map C on Z that gives a Kolmogorov decomposition of A, then there is a unitary operator

Some applications

Stinespring dilation theorem

See also

References

- D.E. Evans and J.T. Lewis, Dilations of irreversible evolutions in algebraic quantum theory, Comm. Dublin Inst. Adv. Studies Ser. A, 24, 1977.

- B. Sz.-Nagy and C. Foias, Harmonic Analysis of Operators on Hilbert Space, North-Holland, 1970.